Main information:

Kunst- und Wunderkammer (Chamber of Art and Curiosities)

The Kunst- und Wunderkammer at Trausnitz Castle is a branch of the Bavarian National Museum.

Chambers of Art and Curiosities were the precursors of today's museums, their contents reflecting the pre-scientific world view prevailing in the 16th century: in that era a plum stone finely carved by an artist was as much of a curiosity as an exotic animal covered with a protective armour.

The "Trausnitz Castle Kunst- und Wunderkammer" documents the long tradition of chambers of art in Bavaria assembled by the Wittelsbach dukes. In 1565 Duke Albrecht V had already founded one of the most important chambers of art in Europe in Munich, which with over 6,000 items was as comprehensive as the Habsburg collections in Ambras Palace and those of the Saxon electors in Dresden.

Albrecht's son and heir Wilhelm started a similar collection in Landshut, assembling artistic, exotic and unusual items in the "Young Chamber of Art" at Trausnitz Castle. When he became duke and moved to Munich in 1579 he took the Landshut collection with him and combined it with his father's Munich Chamber of Art.

The present museum – organized on the basis of archive records – illustrates the function in those days of an archive of artistic and curious items, a complete collection of treasures and valuable furnishings, arrangements of precious objects and paintings: " … so that, through frequent perusal … you can rapidly, easily and securely acquire new knowledge and great wisdom." (Samuel Quiccheberg, adviser to Duke Albrecht V, 1565).

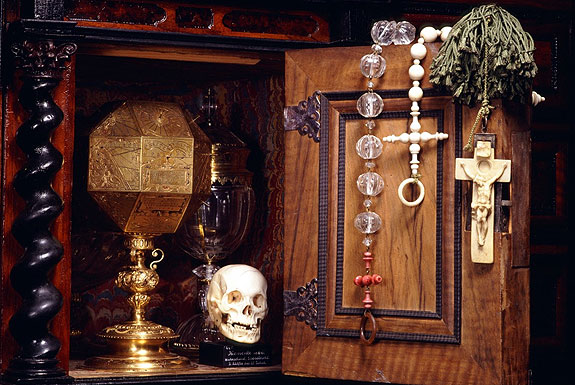

In almost all the aristocratic chambers of art and curiosities the exhibits were organized in four categories: artificialia, naturalia, exotica and scientifica.

Artificialia – curious works of art

In this system artificialia are objects made by man, the best of which represent the perfection of naturally beautiful material through its transformation into an artistic object. Goblets made of rock crystal, serpentine vessels and amber cabinets are works of art of this nature.

Appreciation of the beauty of nature is typical of the Renaissance, as demonstrated by bronzes of animals from this time. The interest in the artistic representation of nature stemmed from a knowledge of antiquity: rediscovered Roman and Greek sculptures, publications on the ancient buildings and their ornamentation and old coins with portraits provided the aristocratic collectors with information about ancient works of art. Sculpture with its three-dimensional beauty ranked above painting as an art form.

Naturalia – the wonders of nature

Augustine had already described nature as "God's first true and ever-open book". Anomalies, monstrosities and inexplicable natural phenomena were seen, valued and even feared as hidden signs of God and were by no means mere curiosities in the modern sense. There was no systematic classification of plants and animals, since it was not until the 18th century that such a system was developed. In the Renaissance natural objects were thus classified according to their origins in the kingdom of minerals, plants and animals in the water and on land.

Hidden meanings and magic properties – stones which indicate poison, roots for making magic potions, the horn of the unicorn – featured prominently among the naturalia in chambers of art and curiosities. Strange animals and unfamiliar plants from newly discovered parts of the world aroused the curiosity of the visitor and were at the same time a status symbol of the collector because of their rarity.

Exotica – curiosities from foreign lands

Since the discovery of the Americas and the landing of the Portuguese in India captains and merchants had brought back sensational riches and exotic things, flora and fauna “von den newen Inseln” (from the new islands). Objects of material value such as gold, precious stones and spices made up the bulk of such imports, yet coveted rarities from heathen lands reached European ports as extra cargo.

From Lisbon, Antwerp, Genoa and Venice, they were distributed to the Kunst- und Wunderkammern (cabinets of art and curiosities) of Europe. The missionaries accompanying the explorers also sent their patrons exotic things. With branches in all new areas, Southern German banking and mercantile houses such as the Fugger and Welser families were responsible for conveying the bulk of the Exotica to Bavarian art cabinets. Presents from Habsburg relatives and from the Medici as well as objects sent by Jesuit missions also contributed to an amazingly diverse collection of foreign exotic marvels.

Scientifica – science classifies the curiosities

"Everything measurable should be measured." This principle, first formulated by Nicolaus Cusanus in the mid-15th century, was put into practice in the age of the Renaissance. The development of astronomy, physics, navigation and cartography went hand in hand with major progress in the development of scientific instruments.

As man tried to determine the coordinates of his own fate as well as those of any given location on land or at sea, various types of research were initiated, the means and results of which were collected in the chambers of art. Magnificent clocks and machines, complicated astrolabes and compasses, maps and globes were an established part of the aristocratic collections. Amazement at the wonders of the world was superseded by a desire to record and classify them according to a rational system. The aristocratic collectors not only admired the complicated mechanisms and aesthetics of the new instruments, but also hoped they would lead to new discoveries about a world governed by causal relations.

With the kind permission of the Bavarian National Museum Munich

© Text and pictures: BNM Munich

Facebook Instagram YouTube